When Have Journalists Become Fans?

I asked Declan Rice for his opinion/

Although educated to be impartial, a journalist is often carried away by emotions. For a journalist is just a man. When there are emotions, there is a bias. It is, therefore, quite expected for a journalist to lose shit and scream when their team scores an equalising goal in stoppage time. While journalists have always supported their national football teams, today, due to the specific environment they work in, they almost have no choice but to be fans. Truth is not the aim anymore.

Hear me out!

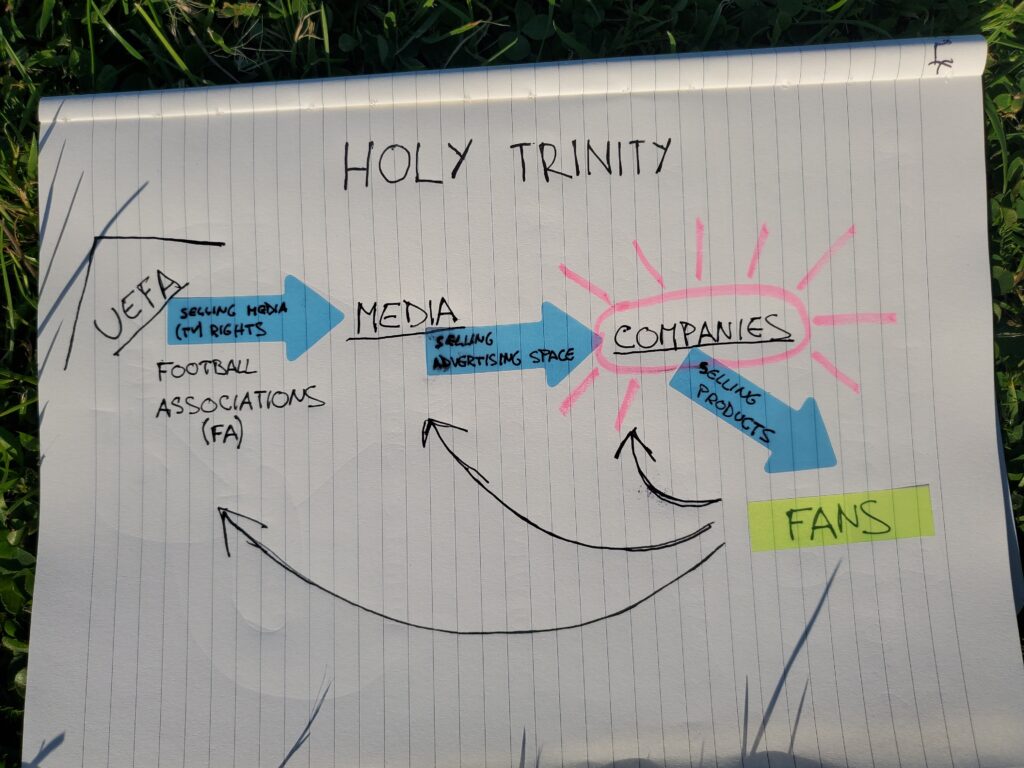

The Holy Trinity of European football consists of the following:

· UEFA (Union of European Football Associations)

· Media

· Companies

Long story short — UEFA sells TV rights to the media, the media sells advertising space to companies, and companies sell products to fans. That is the procedure. Fans — often deluded and unaware — without taking any credit for it, are running the whole show. For UEFA, they are fans. For the media, they are visitors. And for companies, they are customers.

During the European Championship, companies often build their brands’ campaigns on nationalism. What differentiates the most famous brands from the rest is the idea customers attach to a brand. Most countries have a brand of beer or some other drink that in customers evokes a feeling of national pride, success or heartiness. Football fans choose a certain brand of beer not because of the taste but because it gives them a feeling of belonging. It is not about the beer; it is about loyalty. A brand ignites emotions in customers. People buy with emotions, not with logic.

Companies — let’s unravel it — advertise in the media. It is usually in the halftime of a match when we see on TV those beer advertisements that encourage fans to lift their flags high and sing their anthems loud. At the same time, advertisers, as a general rule, manipulate the truth. They make fans believe their product is the best for them. They don’t say, “We sell crap beer, but it is cheap and you are a cheap cunt, so you might like it.” Instead, they use stupid but effective slogans such as, “Beer that is made for you.” In a perfect world, a TV commentator reporting on a match or a journalist covering a press conference shouldn’t be affected by the business connections between the media they work for and the companies that advertise their products in their media. However, once a media outlet and a company strike a deal, a journalist, more often than not, lose their ability to stay impartial. A company that pays big money for a minute of advertising space in a certain media outlet cannot be open to a journalist’s scrutiny anymore. For the media outlet and the company are now partners. Journalism is a victim of the media business. And the crime usually happens as subtly as possible. A journalist gets so exposed to the influx of company’s information about the brand that they stop questioning it all together. A company is always full of praise for their brand. There are various tools companies use to shower journalists with candies, such as press releases, press conferences, press trips, etc. A journalist, through appropriate education about the brand, gets inclined to believe the brand really is top-notch. The final step the company wants to achieve is not creating product awareness, but changing of the whole environment. Beer and other ‘football’ brands thrive on a strong nationalistic atmosphere, and journalists become part of the uplifting machinery. They become fans because, with impartiality, they can’t ignite emotions.

And fans buy with emotions, not with the logic.

UEFA — the one that sells TV rights to the media — plays the role as well. President of UEFA, Aleksander Čeferin, opened his message to the accredited journalists with: “Your role at EURO 2024 will be instrumental in bringing the unparalleled excitement of the tournament to audiences across the globe.”

Why did then Arlind Sadiku, a journalist from Kosovo, got his accreditation cancelled after acting as a fan? Arlind — who I met in Doha in 2016 when Kosovo became a member of the International Sports Press Association — the other day at the match between Serbia and England looked towards the Serbian fans and made the ‘eagle’ gesture — a symbol that represents the double-headed eagle on Albania’s flag. UEFA axed his accreditation.

Arlind told me: “I was provoked every time with Serbian known political chants, ‘Kosovo je srce Srbije’ (Kosovo is the heart of Serbia), and during a live report in affect I did an eagle sign, which is official symbol of Albania at Euro 2024.”

Even though Arlind’s situation is coloured with a bloody history of two nations — Serbians and Albanians — and with personal trauma caused by the war in Kosovo, with his gesture he triggered, as Čeferin said, ‘unparalleled excitement’ among Albanian fans.

If a journalist plays the role of the one who is bringing excitement, then journalist is a fan. When a journalist becomes a fan, they identify with a national team they support, and they don’t see it as an ‘Albanian team’, or ‘Croatian team’ but they see it as ‘us’. They say things such as, “Our team scored the goal,” or “We are playing good.” Once identified with the team and country, a journalist cannot see a situation clearly and be impartial. For when there is a ‘we’, there is also a notion of ‘them’. Just remember how football players get into a fight on a pitch over a referee’s decision — one set of players is convinced they are right, and the other set of players is convinced they are right. They are both ready to go all the way to prove their point. The same blindness affects a TV commentator or a reporter when they become part of the team.

At the same time, the England team believes they are getting too much of criticism from the media. After England drew against Denmark, Declan Rice, in an interview, asked the media for love. Now — you will hardly ever hear an English commentator — even on the national BBC — saying ‘we’. It is ‘England’ for them. And in fact, that might be the reason England national team always come short on big tournaments — there is no unity between the players, the media and the fans. But there is impartiality instead. I guess we need to ask ourselves what we want to achieve as a species — do we seek truth or do we seek excitement?

And so I went to Cologne to an England press conference a day before their final group stage match against Slovenia. Declan Rice was there to speak out, so I told him: “Declan, I’ve heard recently that you were asking for love from the media so the team could perform better. Which makes sense. I have been to quite a few press conferences from different national teams. And in fact, some journalists in some countries do act like fans rather than journalists and they give love unconditionally to players. You, however, perform in a quite a different media environment where journalists are more like journalists. I would like to ask you how you would like to see that balance. Would you like to have full support or would like to be criticised? How do you see the situation?

“As a player, you read stuff. Naturally, for a young player, stuff can play on your mind and it’s probably better to read stuff that is way more positive than negative.”